Avatar: The Way of Water may arguably be the greatest “love letter to the ocean” in cinema. James Cameron’s visually stunning and thematically moving film captures the beauty and horrors in our planet and what it means to be family to our own kind, the creatures around us, and this very earth. After watching the film, I couldn’t help but notice the many layers of water philosophy and symbolism—and to finally write one sweeping article on my reflections and findings.

*Disclaimer: major spoilers ahead.

In this two-part article, we will explore “The Way of Water” in James Cameron’s long-awaited sequel and its connections to global wisdom traditions (particularly East Asian, Orthodox Christian, and Maori). Both concepts of “The Way” and “Water” are permeable and multifaceted. Since there are many directions that we can take, I’ve divided this two-part article into three sections, each dedicated to a sentience in the Avatar universe: Pandora, the Tulkun, and the Na’vi. These are the three ‘minds’, so to speak, that will lead our way in exploring the philosophy of water.

Avatar: The Way of Water may arguably be the greatest “love letter to the ocean” in cinema.

The first section, “Pandora and the Way of Water,” will set the stage for the second and third sections with its conceptual foundations–such as the framework of the Way and characteristics of Water in Chinese, Orthodox, and Maori traditions. The Way is seen as cosmic and divine, and Water as universal and essential. These are the contents of Part One.

The final two sections, “Tulkuns: The Paradoxical Virtues and Mythos of Water” and “Na’vis: The Unified Virtues and Cycles of Water,” will focus more on the philosophy and symbolism of water in particular characters and events in Avatar 2. This includes (A) the Tulkun relationship between passive and active natures of Water, in their connections to Payakan and SeaDragon; and (B) the Na’vi relationship between the unifying and cyclical natures of Water, in their application to the Metkayina and Omaticaya. I also include some of their fascinating relationships with sea lores. These are the contents of Part Two.

*Note: we often see ancient wisdom traditions in two ways: (1) negatively, as primitive, barbaric, and superstitious, and (2) positively, as foreign, exotic, and “borrowable” (giving rise to what scholars call “Western Esotericism,” a mixture of spiritualities adapted into modern life). So, #1 has done us a disservice and #2 can do them a disservice by distorting them: imitating and depicting these traditions incorrectly through our modern, western minds. This is a process called Orientalizing. So, keep in mind that this article will only provide a glimpse, a surface, or an entry point into long-lasting and self-sufficient philosophies that are embedded in many great cultures (cohesive and distinctive in their own right), inviting us to wonder, mystery, and cultivation of intellectual humility.

I. Pandora and the Way of Water

The film introduces both the Way of Water philosophy and the underwater scenes when the Omaticaya children begin to learn freediving from the Metkayina children. As they dive into the waters, they encounter the wonders of new flora and fauna: a plethora of beautifully diverse creatures and habitation. We as the audience begin to see the Way of Water—its life, its work, its beauty. And as the movie showcases footages of Lo’ak being trained by Tsireya to breathe and dive, she recites the axioms or proverbs of the Metkayina:

The Way of Water has no beginning and no end.

The sea is around you and in you.

The sea is your home, before your birth and after your death.

The sea gives and the sea takes.

The Way of Water connects all things. Life to death. Darkness to light.

These sayings express that The Way and Water are bigger than us yet are part of us. Implicit in these underwater scenes are James Cameron’s visual queue on how water connects all things–all elements and creatures, before our birth and after our death–in Pandora: air (breath) to provide survival to inhabit the waters; fire (Sun) to provide energy, light, and warmth in the waters; and earth (Pandora) to provide a home for the waters.

Now, the descriptions of The Way of Water are strikingly similar to how Chinese Philosophy and Eastern Orthodoxy would describe “The Way,” or the Tao in the former and God in the latter. For example, one can simply replace the phrases “The Way of Water” and “the sea” with the nouns above: “The Tao connects all things” and “The Lord gives and the Lord takes away.” Both signify a Way of life or being of the cosmos and the divine. And man only imitates or participates in this Way.

The Way in both Chinese Philosophy and Eastern Orthodoxy is not meant to be defined—it is not reducible to just doctrine or principle—but meant to be experienced. As such, the Way is usually described, like in Avatar 2, through proverbs of personification and paradoxes. The Na’vi, then, recognizes that the Way of Water has cosmic, even divine, qualities.

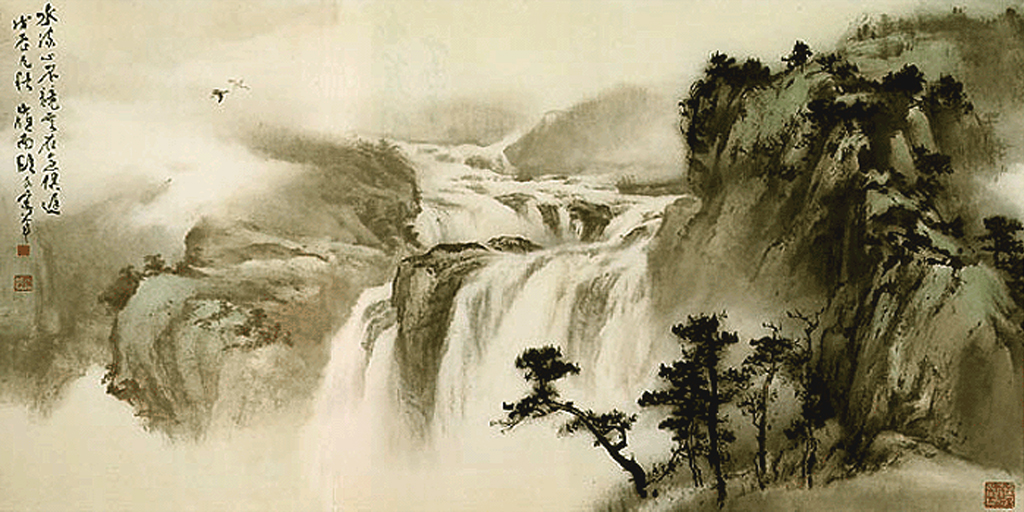

“Way” and “Water” in Chinese Philosophy

Before we move on to how the Way of Water connects with the Tulkun and the Na’vi ways and particularly the story of Payakan and the Sullies, I must clarify that there’s a difference of understanding or articulating the Way in Confucianist and Taoist philosophies, which can enlighten us on how the film expresses the Way of Water as (for lack of better terms) both a natural vs. a moral kind of force.

For Confucianism, the Way is a kind of force that makes human beings moral beings. The Way can be pursued by oneself or instructed to others. Hence the main Confucian text, The Analects, focuses on practicing and educating virtues of benevolence, filial piety, ritual etiquette, etc.

For Taoism, however, the Way is a kind of natural force. The main text, Tao Te Ching, describes it as “nameless” (ineffable or beyond description) and seems to be in everything and gives being to everything, while at the same time is also described as “nothing” (not that it doesn’t exist, but it is characterized as non-active).

The greatest metaphor for this is water. Water embodies “non-action.” Water is paradoxical in that, like the Way or Tao, it gives everything but doesn’t sacrifice anything; it is passive yet active. To quote the proverb from Tao Te Ching, “The Way is empty, yet use will not drain it.” And to cite the be like water quote from Bruce Lee, water is “empty… formless… shapeless…” yet it always “flows or crashes” in everything.

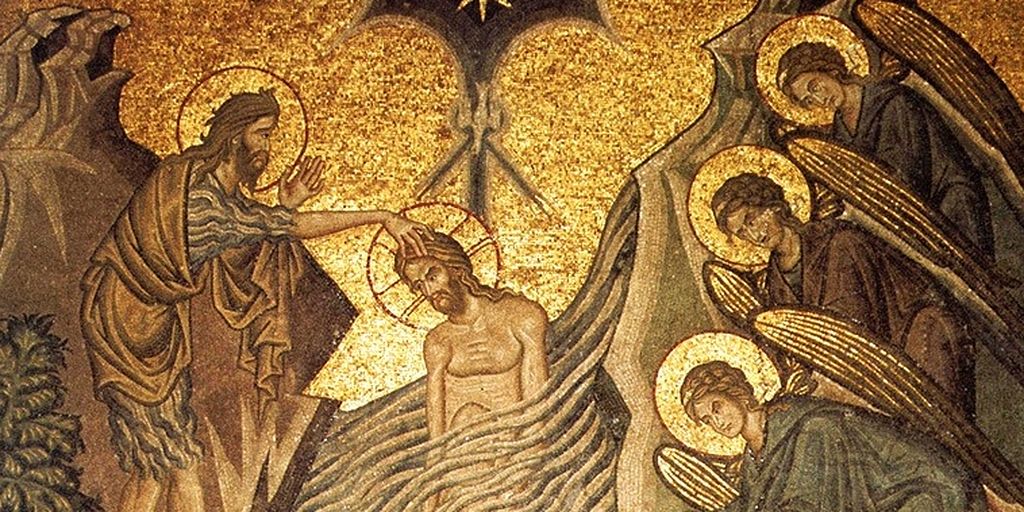

“Way” and “Water” in Eastern Orthodoxy

In some Chinese translations of John’s Prologue, it is written: “In the beginning was the Tao, and the Tao was God, and the Tao was with God… and the Tao was made Man.” So, like Taoism, the Way or Tao is a transcendent principle, but it is at the same time a tangible person. The Early Church called themselves Followers of the Way, and in Orthodox Christianity, this ethos of belonging in vs. maligning the Way takes primacy. Christianity is a way of life that is filled with deep lore and rich with symbolism and archetypes. The God-Man or Christ refers to himself as Living Water and one must be engrafted into him through baptismal water.

Alexander Schmemann, an Orthodox presbyter, in his book Of Water and Spirit: A Liturgical Study of Baptism, explains that there are three “cosmic” elements of water, which we also see in Avatar 2:

Water is undoubtedly one of the most ancient and universal of all religious symbols… Three essential dimensions of this symbolism are important.

- The first one can be termed cosmical. There can be no life without water, and because of this the ‘primitive’ man identifies water with the principle of life…

- But if water reflects and symbolizes the world as cosmos and life, it is also the symbol of destruction and death. It is the mysterious depth which kills and annihilates… the very image of the irrational, uncontrollable, elemental in the world. [On both principles:] such is the essentially ambiguous intuition of water in man’s religious worldview.

- And finally, water is the principle of purification, of cleanliness, and therefore of regeneration and renewal. It washes away stains, it re-creates the pristine purity of the earth.

[On all principles:] Life, Death, and Resurrection: united and “held together” in their inner interdependence and unity in this one symbol.

Of Water and Spirit, 39.

Thus, the Way of Water, akin to the Metkayina philosophy, connects all things: life to death (principles #1-2) and darkness to light (principle #3 or renewal).

Whakapapa of Water in Maoridom

While we can say that the Way is cosmic and divine, which is similar to Water being universal and essential, in Maori cultures that inspired the Metkayina culture, Water is also genealogical. (Later on, after discussion on the Tulkun and the Na’vi, we’ll see how these concepts are embodied in the film.)

The Maori universe is a gigantic kin, a genealogy… a veritable ontology.

“Hierarchy and Humanity in Polynesia,” 195

What this means is that the universe has an origin and an ancestry, or what the Maori call a whakapapa. Everything is holistic and interconnected—life and death, darkness and light. And the whakapapa of water, according to one chant, is generated from Ranginui (the heavens) and Papatuanuku (the earth). The earth and the heavens, when they are complemented, generate myriads of creatures. In this sense, the history of the cosmos is closely connected to the history of human ancestry. And speaking of myriads of creatures, whales too are given the status of ancestor.

*Note: my upcoming article, “Pandora and a Theology of Ecology” (tentative title), explores these ideas in more detail.

Click here to read Part Two, which covers the philosophy and symbolism of water via the Tulkuns and Na’vis in Avatar 2.

Leave a comment