Continue our philosophical exploration from Part One, which covers three important distinctions to help us think well about eco-theology: (1) nature ecology vs. human ecology; (2) instrumental value vs. intrinsic value, and relational value; and (3) creation vs. environment.

II. Sacrality: Mother Nature

Matter and spirit are one, and Eywa is both.

Andrew Stephen Damick observes that many contemporary, rather than historical, forms of Christianity separate both. Therefore, spirit (humans) must be separate from matter (nature), so that either

A. Humans should be removed from nature (intrinsic value approach)

or

B. Humans should be exploiting nature (instrumental value approach)

This is a false dichotomy, since humans, as the pinnacle of creation, must be the priests of creation—or mediators in sacred nature.

For na’vi’s, nature is sacred. Na’vis have what is equivalent to temples and cemeteries, such as the Tree of Souls and the Cove of Ancestors, understanding that there is holiness of place. This means that nature does not only have a functional purpose but spiritual import. Such a view also depends on the notion of Mother Earth, for Pandora is not only spiritual but mystically personal.

What does it mean that Eywa is the Great Mother or All-Mother?

The notion of Mother is associated with the nourishment, flourishing, and generation of life; perhaps it’s sometimes accused as inferior to patriarchy, but Eywa is an embodiment of maternity and matriarchy. In other words: Eywa embodies queenship, protectorship, life force… like Neytiri and Ronal who were boldly carrying a child in their womb while holding a weapon in their hands.

Eywa is mighty. And Eywa is Gaia.

What is called the Gaia Hypothesis is well-known to suggest that Earth is a living organism that maintains the balance of the ecosystem. In fact, Eywa was called Gaia in the first script of Avatar, “Project 880.” Though both centers around planetary awareness/consciousness and interconnectedness, Eywa has a ‘will’ and an ‘ego.’

Like the figure of Papatuanuku in Maoridom (embodiment of earth who gave birth to all life), Jord in Old Norse (personification of earth), and Gaia in Ancient Greece or Terra Mater in Ancient Rome (also a personification of earth and mother of all life), the maternity of Eywa has divine and cosmic implications. Three noteworthy and cosmic-scale ones are:

The being of Eywa…

- Endorses Culture, for a mother generates family, and family generates culture

- Provides Laws, for a mother knows what is good, bad, and wise, and these are the foundation of laws—more on this noted in Section 3

- Interconnects, Sanctifies, and Eternalizes All Beings, after all, she is a mother-goddess

Why does this matter for human ecology and nature ecology? Here’s a few words from Oglala Sioux tribe member Ed McGaa who wrote on Native American spirituality:

“Our survival is dependent on the realization that Mother Earth is a truly holy [and] living being. Think of your fellow men and women as holy people who were put here by the Great Spirit. Think of being related to all things! With this philosophy in mind as we go on with our environmental ecology efforts, our search for spirituality, and our quest for peace, we will be far more successful when we truly understand the Indians’ respect for Mother Earth.”

Mother Earth Spirituality

But Mother Earth can also be killed, and her survival is in our hands. And since our survival is also in the hands of Mother Earth, since we can kill her, our survival is also in our hands.

*In the Section 4 of my first article, “The Philosophy and Symbolism of Water,” I made connections on how Earth is Pandora.

III. Technology: Manmade Nature

Jake once queued Eywa under Tree of Souls:

“Look into [Grace’s] memories… See the world we come from. There’s no green there. They killed their Mother.”

Today, we cannot return to a state of pre-industrialization. We cannot reverse technology and simply endorse anti-technology. In fact, this is also not the Na’vi Way.

The na’vi does have technology, albeit renewable, ecofriendly, and organic. Bow and arrow could be said to be a basic technology for hunting. Even their architecture, a basic technology for dwelling, weaves together patterns of nature and is weaved into the habitats in nature. This is called biomimicry.

*I wrote an article on “Desire, Happiness, and Three Laws of Eywa” (laws preventing the construction of roads, wheels, and metals) to highlight that the problem with ecological crises is also the problem of our inner selves. We desire things for our happiness, including things that harm nature for our human desires. Read more to explore the na’vi solution, which is in fact Eywa’s solution.

So, technology is inevitable. Technology is also “neutral,” meaning that it is neither positive nor negative; only the usage is, relative to nature’s relational values. But with excess of harm on nature ecology to benefit human ecology, we now face several crises: the loss of biodiversity and the rise of pollution.

But also, we know about how to prevent harm and how to do good by understanding the cosmos—its nature, its current problems, and its feasible solutions, through using technology (Section 2).

Additionally, we do so by revering the cosmos—its beauty, its divine qualities, and its sacramental reality, through “seeing” sacrality (Section 3).

Now, we come to whom we can consider the archetypes of mother nature (#2) and manmade nature (#3): Eywa and Grace. The marriage of both archetypes give birth to the archetype that joins sacrality and technology: Kiri.

IV. Eywa, Grace, and Kiri

The way forward is to embody the values of Eywa and Grace, which is epitomized in Kiri.

Here, I’ll synthesize the previous points, which are evident points in the film:

- The Way of Eywa: to revere the theological aspect of the cosmos

- The Way of Grace: to understand the ecological aspect of the cosmos

We are now brought back to Section 1 where I pointed out that what is ecological is cosmological, and what is cosmological is theological.

Grace is the person that seeks to understand the cosmos using technology (such as tools of natural and human sciences), while Eywa is the being that underlies the cosmos infusing sacrality. This is the Na’vi Way. The marriage between the two has given us Kiri.

Kiri, born of Grace and gift of Eywa, is still a child, but she’s a special kind of child. She grows up with much visitation to Grace and much sensitivity to Eywa.

On the former, Grace has much influence on Kiri, who’d learn from her mother’s research videos about the ecological life of Pandora. Kiri is quite the “natural scientist” herself, suggesting to Mo’at to use yalna bark to heal Neteyam because it stings less, using her knowledge of nature for good use. Finally, Kiri also uses Grace’s necklace and would collect items she discovered (rocks, feathers, pebbles, etc.), which I call samples, for her clothing.

On the latter, it is evident that she has a deep connection with Eywa and Her world, and perhaps even more so than tsahiks. So much so, that even Ronal, a tsahik like Mo’at, was in awe of Kiri when she played with and directed a herd of glowing fish one evening. I wouldn’t be surprised if Kiri would be the “ultimate” tsahik in future movies, being both born through Eywa’s sacred will yet also a human scientist.

Childlikeness and Children

There is one thing that stuck out from Kiri (and other children who share her love of nature, such as Tuk). James Cameron pointed out what he commends as the childlikeness, as opposed to childishness, of Kiri:

“The goal of either of my major projects right now, Super/Natural or Avatar: The Way of Water, is to remind us how important nature is to us, and put us back into that kind of childlike perspective where we have this sense of wonder and connection to nature. Kids feel connected to nature. They’ll go out, they’ll come back filthy, they’ll come back having caught things and played with them and studied them. All kids are natural historians, natural scientists, and then they leave it behind and we move on and we live in an increasing state of nature deficit disorder.”

“James Cameron Q&A” with Richard Trenholm

Beyond childlikeness, I also commend the care for children. Children are special in the eyes of Eywa (I know this not only from her Three Laws) but also simply for being the Great Mother who is committed to life. And life is from generation to generation.

Earth care and human care must be one, just as Pandora care and na’vi care are one. Both should not be neglected nor in tension but be wedded in an organic union.

So now we can do our part, as the na’vis do, to honor the planet and honor the people—to help conserve and restore nature ecology and redirect desires and praxis of human ecology. (One could begin by scrolling down the Resources page!)

Choose to love our future children, for they will either live in our garden or our wasteland. With the commitment of Grace to understand the cosmos and the commitment of Eywa to nourish the cosmos, and the childlikeness of Kiri, we take part in the universal love of the Great Mother and the rich eco-theology of Pandora. This is in line with Dostoevsky’s masterpiece, The Brothers Karamazov:

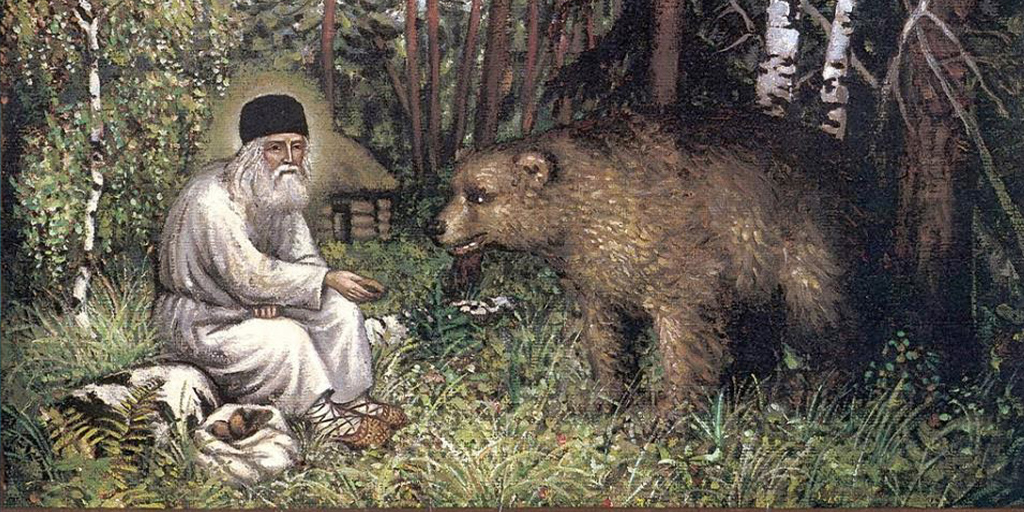

“Love all creation, both the whole and every grain of sand. Love every leaf, every ray of light. Love the animals, love the plants, love everything. If you love everything, you will perceive the divine mystery in things.”

Elder Zosima in Book IV

Happy Earth Day!

– Pandoran Philosopher

Leave a comment